Ziad Fahmy, Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation through Popular Culture. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Jadaliyya: What made you write this book?

Ziad Fahmy: Growing up in Alexandria, Egypt, I experienced firsthand the marked difference between the modern standard Arabic (MSA) that I was taught in school and the colloquial Egyptian I spoke with my parents, relatives, and friends. In elementary school, I struggled with the complex grammar rules and regulations we had to learn, which had little relevance to the everyday language we spoke. Though I was obviously aware of the dissimilarity between fusha (classical Arabic) and ‘ammiyya (spoken dialect), I never consciously and/or actively thought through the cultural and historical implications of this linguistic split until graduate school. After familiarizing myself with some of the theoretical readings on nationalism, I quickly realized the importance of this linguistic split on the development of national identity in Egypt and the rest of the Arab world.

Niloofar Haeri’s Sacred Language, Ordinary People (2003) and Walter Armbrust’s Mass Culture and Modernism in Egypt (1996) were instrumental in crystallizing my thoughts on the importance of colloquial Egyptian culture and the burgeoning Egyptian mass-media for any attempt at understanding the history of modern Egypt. As I began conducting my research, my initial intent was to focus almost entirely on colloquial Egyptian satirical magazines and newspapers, which were quite plentiful from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century. But I soon realized the importance of music and the comedic theater in the urban culture of turn-of-the-century Egypt. This made me expand the scope of my research to incorporate the colloquial culture of Egypt as an entire media system, which, as I attempted to show in my book, was instrumental in constructing a modern Egyptian national identity.

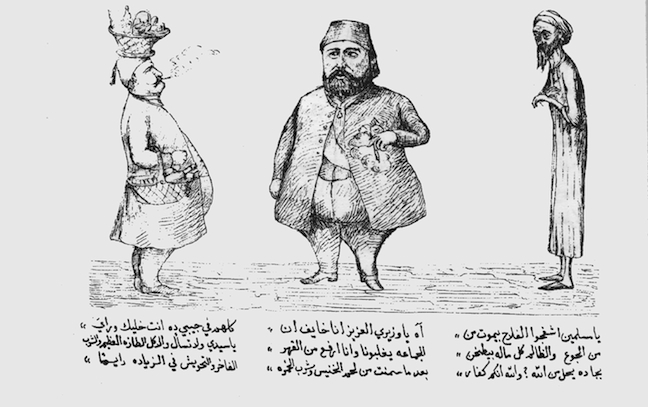

[Cartoon: “Isma‘il’s Corruption.” Source: From Abu Naddara Zarqa’, 22 October 1878. Image via Ziad Fahmy.]

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does your book address?

ZF: As I alluded to above, historians of the Modern Middle East have neglected the role of colloquial Arabic, either in its written or oral forms, relying almost exclusively on written fusha texts and sources. Because Egypt’s literacy rates were so low at the turn of the twentieth century, focusing entirely on fusha texts tilts the historiography towards an elite perspective. My book argues that modern Egyptian national identity coalesced on the popular level mainly through mass-produced colloquial cultural production. My research considers both the urban evolution of mass-produced colloquial Egyptian songs, plays, and newspapers as well as their impact on the popular level. Because these new media relied on colloquial Egyptian Arabic, as opposed to MSA Arabic, they exerted a tremendous influence on mass opinion, which inevitably shaped urban mass-practice.

Ordinary Egyptians also critically engages with some of the more general theories of nationalism. Print-capitalism, as elaborated on by Benedict Anderson, was an important component in establishing national identity. However, in Egypt, where literacy rates were/are relatively low, non-textual mediums play(ed) a much greater role in shaping identities. During the 1910s and 1920s, the increasing availability of non-textual transmission media, like the phonograph and a music industry producing records for mass consumption, arguably contributed more than any print media to the molding of national tastes, leading to the formation of an increasingly national identity. For this reason, I devised the concept of media-capitalism as a more appropriate term for examining the cultural processes taking place, since it is wide enough to incorporate all forms of mass media, including print, performance, recording, broadcast, and eventually web and satellite media.

Certainly in the Egyptian case, and I suspect in other cases, a synergetic combination of all available media simultaneously helped shape the “modern” identities of cultural consumers. Though my study is focused on Egypt, I hope that it will have a broader impact, in that its methods may be extrapolated to other regions of the Arab world where the varied colloquial Arabic dialects and their effects on territorial nationalism are similarly understudied. This approach promises to nuance and contextualize the study of nationalism in the Arab world and provides a possible explanation for the failure of a supra-state Arab nationalism.

[Ziad Fahmy. Image via the author.]

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

ZF: I hope historians and other scholars working on Egypt and the rest of Middle East will read my book. Ideally, of course, I wish that Ordinary Egyptian is also read more broadly by scholars of nationalism and popular culture. In writing and revising Ordinary Egyptian, I made a concerted effort to make my prose as accessible as possible, in the hope that the book can be accessible not only to graduate students but also to undergraduate students.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

ZF: I have begun research on a second book tentatively titled: Listening to the Nation: Mass Culture and Identities in Interwar Egypt. Temporally, Listening to the Nation continues where Ordinary Egyptians left off, though my focus will be almost entirely on listening and sound culture. It is of course too early to tell which direction this project will take. If the sources allow, radio will feature prominently in the book, though I will also attempt to analyze the changing urban soundscape of interwar Egypt.

[“Egyptian crowds with Italian flag during 1919 Revolution.” Source: From L’Illustration (Paris), 3 May 1919. Image via Ziad Fahmy.]

Excerpt from Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation through Popular Culture

Mundane Nationalism

Egypt’s new mass media reflected on relevant everyday political, economic, and cultural concerns and amplified them on the national stage in a comprehensible, locally pertinent, and entertaining form. The repeated themes of many of these media included bemoaning the lack of economic opportunities for native Egyptians, portraying the economic exploitation of Egyptians by foreigners, warning of perceived declines in national “morality,” satirizing and at times insulting British and native officials, and rousing patriotism and a sense of collective national solidarity.

However, the most effective way that national identity and a sense of nationhood were absorbed was not only through these overstated themes and methods but also through the mundane media portrayals and representations of everyday “national” life and the internalization of these modes in actual practice. As Michael Billig describes in Banal Nationalism, nationalist ideology “might appear banal, routine, almost invisible,” but these “subconscious” matter-of-fact representations create a commonsense “naturalness of belonging to a nation.” Billig explains that often there is “continual ‘flagging,’ or reminding, of nationhood,” because on a daily basis, citizens are reminded of their national identity. This reminding, however, is “so familiar, so continual, that it is not consciously registered as reminding.” Mundane and unstated representations of Egyptianness abounded in most forms of mass culture, where “Egyptians” distinctively spoke and acted and were clearly, though tacitly, differentiated from non-Egyptians.

Most of the media examined in this book implicitly addressed their listeners, viewers, and readers as members of an Egyptian “nation.” To be sure, the most influential aspect of vaudeville and the satirical press was not necessarily the outwardly nationalistic messages of many of their articles, cartoons, and dialogues but the recurring and mundane representations of colloquial Cairene as the de facto dialect of all Egyptians and the implicit understanding that flawlessly speaking and understanding it was the basic marker of a “modern” Egyptian national identity. Only an “authentic” ibn or bint al-balad (son or daughter of the country) would use Egyptian Arabic and grasp its multiple meanings and nuances and hence participate in this new mass-produced colloquial culture. In fact, many of the comedic dialogues depicted in political cartoons and vaudeville repeatedly contrasted the mispronunciations of foreigners—who often played unsympathetic or villainous roles—with the “correct” pronunciation of affable Egyptian characters. This repeated portrayal of Cairene as the only “authentic” Egyptian accent reified it as an unofficial dialect of all Egyptians, even if back in the villages and towns of the Sa‘id more localized modes of expression were used. By way of media capitalism, Cairo’s dialect and culture were overwhelming—colonizing, if you will—the multitude of other localized dialects and cultures in Egypt. Thus, paradoxically, Cairene Arabic was the primary tool for nationalist, anti-imperialist discourse, and simultaneously, through internal colonialism, it imposed its own culture on the “nation.”

The Sensorium and the Public Sphere

The efficacy of the new mass media and their potential for mass mobilization were best demonstrated during times of national crisis. The 1906 Dinshaway incident and the 1919 Revolution in particular reveal how all forms of mass media functioned together to effectively document, memorialize, celebrate, and mobilize on a national scale. The growth of popular Egyptian mass culture was the pivotal factor in the popularization and dissemination of an Egyptian national identity. The evolution and universalization of a colloquial Egyptian middle culture, made possible especially through the utilization of sound and audiovisual media, allowed for a shared and “uniquely” Egyptian cultural landscape. It is primarily within this nonofficial web of vernacular mass culture, driven in large part by media capitalism, that Egyptian national identity was widely disseminated and popularized.

One crucial aspect of this study was the critical role that coffee shops played as cultural hubs. Differing mass media, from newspapers to recorded music, publicly merged and were negotiated and digested in the coffeehouses. Many of the songs initially written for musical and comedic plays were recorded and played or performed by street musicians at coffee shops and even in the streets and on the sidewalks. The role of the thousands of urban cafés and other public meeting places in the broadcasting and reception of these new cultural productions is central to understanding the potency and effectiveness of this developing nationwide culture. Indeed, coffeehouses, as Briggs and Burke remarked, “inspired the creation of imagined communities of oral communication.”

However, as discussed in this book, these conversations were never one-sided, because writers of these vernacular media were plugged into the streets and public squares through these very same cafés. As we have observed throughout this study, the entire vaudeville theater industry arose out of the cafés on ‘Imad al-Din Street, where most of the vaudeville theaters were housed. It was through these dialogical “physical” interactions with the people in the streets, marketplaces, and cafés that the writers, musicians, and performers of these media (re)calibrated the subtleties, textures, and flavors of everyday Egyptian life. As Bakhtin cautions, we must not ignore the “social life of discourse outside the artist’s study, discourse in the open spaces of public squares, streets, cities, and villages”; it is in these public spheres that Egyptian mass culture is embodied into everyday life, acquiring its socioeconomic, political relevance and, more important perhaps, its perceived authenticity and contemporaneity.

Indeed, access to any form of knowledge—be it visual, aural, tactile, gustatory, or olfactory—is corporally mediated and acquired through a living dialogical engagement. Or as Bakhtin elaborates, “The single adequate form to verbally expressing authentic human life is the open ended dialogue….In this dialogue a person participates wholly and throughout his whole life, with his eyes, lips, hands, soul, spirit, within his whole body and deeds.” In other words, texts alone are meaningless when viewed in isolation of the socially embodied realities of their production and, more important perhaps, their reception on the street. It is in their interrelationship with social life that texts become meaningfully activated and authenticated as genuinely reflecting popular concerns and realities. As we have seen throughout this book, colloquial Egyptian culture is better equipped to engage in this dialogue with the everyday and hence to guarantee its circulation and popularity.

[Excerpted from Ziad Fahmy, Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation through Popular Culture, pages 170-172. © 2011 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. For more information, or to order the book, click here.]

![[Cover of Ziad Fahmy, \"Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation through Popular Culture\"]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Screenshot2012-01-21at1.07.48PM.png)